Pentachlorophenol is on its way out as a utility pole preservative. Here's what might take its place

Credit: Alex Tullo/C&EN

Wood utility poles are treated with preservatives that help them last decades.

We don’t normally give much thought to utility poles until someone pulls up in a bucket truck to work on one or a spitting power line falls during a storm.

But few things are as useful. Utility poles carry electric cables, copper telephone lines, and fiber-optic internet cables a safe distance from the ground. Streetlights and electrical transformers are mounted on them. They even serve as a superhighway for squirrels and a medium for posting yard sale signs.

In order to last for decades after they are sunk into the ground, wood utility poles need preservatives that fend off termites, fungi, and the elements. Not many chemicals are up to the challenge.

About half the wood poles in the US are treated with pentachlorophenol, known as “penta” in the trade. Penta is “cheap, easy, and effective,” explains Philip Ford, director of technical sales and quality conformance at American Borate, which makes wood preservatives for other applications. The US penta market, according to industry player Koppers, is worth about $40 million per year.

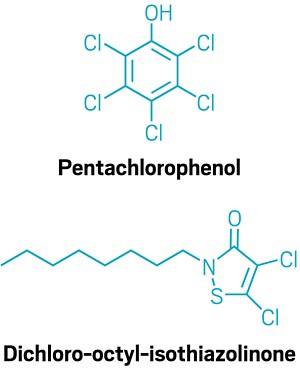

But penta is also a possible carcinogen and is banned in most countries. This has prompted the sole North American producer to announce it will close its plant, in Mexico, by the end of 2021. With the clock ticking, utility pole makers are looking for safer alternatives, such as copper naphthenate and dichloro-octyl-isothiazolinone (DCOI).

Preservatives are applied to wood under pressure in a treatment chamber. Easier-to-treat woods, like southern yellow pine, can be processed with waterborne preservatives such as chromated copper arsenate (CCA), which more than a decade ago was phased out of decking and other domestic lumber uses. Other woods, such as Douglas fir, require oil-based preservatives, like penta, that penetrate better. CCA-protected poles predominate in the southeastern US. Penta-treated poles are more prevalent elsewhere.

In 2015, the Stockholm Convention banned penta, classifying it as a persistent organic pollutant. The convention notes, among other health concerns, that penta is “associated with carcinogenic, renal, and neurological effects.” The US signed but never ratified the treaty, making it one of the few places on the planet where use of the chemical is still allowed.

Jay Feldman, executive director of the environmental group Beyond Pesticides, accuses the US Environmental Protection Agency of dragging its feet on penta despite alarming cancer findings. For instance, he says, in 1999 the EPA found that children playing near penta-treated utility poles have a 2.2 in 10,000 risk of getting cancer, 200 times the acceptable threshold.

When Cabot decided they were going to get out of the business, our phone started ringing off the hook.

Ken Laughlin, vice president of wood preservation, Nisus

“We’re very concerned about the continued use of this chemical in utility poles because it’s so widespread throughout our communities,” Feldman says.

The only North American producer of penta is Cabot Microelectronics Corporation (CMC), at a plant in Matamoros, Mexico. The penta operation tagged along as part of CMC’s 2018 purchase of KMG Chemicals, which was mainly a maker of materials for the electronics industry. It was hardly a core business for CMC.

Last fall, CMC said that implementation of the Stockholm Convention in Mexico would force it to shut down the penta plant as well as a blending facility in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, by the end of 2021. The company considered building a new plant, presumably in the US, but instead opted to shut down the whole business.

Seeing a void it might fill, the privately owned chemical maker Gulbrandsen announced in January that it would build a penta plant at its facility in Orangeburg, South Carolina. “We possess the expertise and technology necessary to effectively manufacture penta in a safe manner at our South Carolina plant and have much of the infrastructure and raw material–handling facilities already in place,” President Eric Smith said in an announcement at the time.

The local community and environmental groups didn’t see it that way. “Inevitably, that plant would have been deemed a Superfund site down the road,” Beyond Pesticides’ Feldman says. Local legislators proposed a bill putting a moratorium on penta manufacture in South Carolina.

Gulbrandsen backed off.

Without a continuing supply of penta, utility pole makers will be forced to find replacement preservatives. Colin McCown, executive vice president of the American Wood Protection Association, points out that local utility companies specify what kinds of poles they buy.

“It’s difficult to guess at what utility companies might choose if they are forced to change,” he says. “For oil-type preservatives other than penta, there are creosote, creosote solutions, copper naphthenate, and DCOI.”

Copper naphthenate and DCOI are generally regarded as environmental improvements over penta. Creosote, which is a mixture of many chemicals, does pose exposure risks.

It is up to utility pole makers and their chemical suppliers to guess where the market will go. Koppers, number 2 in utility pole fabrication, behind Stella-Jones, produces wood preservatives such as creosote—used mostly on railroad ties—and copper-based chemicals. Koppers said it might start making copper naphthenate or secure an outside supply of it.

Copper naphthenate has been around for more than 100 years. In World War II, it was used to stretch out short creosote supplies, according to Jim Gorman, vice president of marketing at the pesticide maker Nisus. It has since been deployed to protect canvas tents and ammunition boxes for the military. Hardware stores sell it to homeowners and contractors.

In 2011, the EPA registration for copper naphthenate on utility poles nearly expired. With no other company willing to submit the paperwork, Nisus saw a chance to get into the business. “We were more in the pest control business but dipping our feet into wood preservation,” Gorman says. Nisus spent about $3 million to gather the necessary documents to secure the registration. It built a plant in Rockford, Tennessee, at a cost of about $4 million.

Even before CMC announced its withdrawal, copper naphthenate had been gaining traction among environmentally forward-thinking utilities on the West Coast. Nationwide, it is used on 2.5–5% of the 2.5 million poles made annually, according to Ken Laughlin, vice president of wood preservation at Nisus.

That market share should expand now. “When Cabot decided they were going to get out of the business, our phone started ringing off the hook,” Laughlin says. “All the treatment plants were concerned about what they were going to do when penta went away.” Nisus says six utilities began specifying copper naphthenate since CMC’s announcement.

Another company that sees opportunity is Viance, a joint venture between DuPont and the pigment producer Venator Materials. The company hopes that its product, DCOI, will gain traction as a penta substitute.

“It’s the first new oil-borne preservative in many decades,” says Bob Baeppler, Viance’s business development manager for industrial products. He believes the chemical’s time has come now that the environment is such a big consideration. “I think you will find it difficult to find anything better than DCOI in that respect,” he notes.

A Viance forebear, Rohm and Haas, developed DCOI in the 1980s. In 1996, Rohm and Haas won one of the first US Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards, for the use of DCOI in a marine antifoulant coating. DCOI has also been used as a fishnet preservative and an algicide for cooling towers, Baeppler says.

Viance’s effort in DCOI for utility pole treatment is relatively new, Baeppler says, but third-party testing suggests DCOI outperforms penta. “We’re still evangelizing to make as many utilities aware as possible,” he says. Stella-Jones is starting DCOI trials at its wood treatment plant in Arlington, Washington.

Still, Baeppler isn’t holding his breath. He points out that CCA was introduced in 1946 but wasn’t used to treat a majority of southern yellow pine poles until 2003. “We’re just on the cusp,” he says. “This is an industry that moves really, really slowly.”

Chemical & Engineering News

ISSN 0009-2347

Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society

http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/cen_latestnews/~3/z8TOHeS9pEY/i14

Comments

Post a Comment